Before getting into this one, I want to make it clear that this is not an invitation to debate the merits of the theory of evolution. For the purposes of this post, it is assumed that evolution, specifically that humans evolved from ancient apes (NOT modern apes--humans are not descended from any modern ape). As for the "it's only a theory" argument, a theory is as close to fact as you can get in science. We don't discount Einstein's theory of relativity or Newton's gravitational theory because they are "only theories", so neither should we reject the theory of evolution on those grounds. If evolution wasn't as close to fact as science will get then it would be the conjecture of evolution, not the theory.

Anyway, continuing on now from the assumption that evolution is a fact:

Do you ever wonder why, if our distant ancestors were hairy apes, we have lost almost all of our body hair? Even stranger to me is how long the hair on our heads grows; I know of no other animal that grows the hair on its head to such ridiculous lengths. (If there is one, please enlighten me.)

In pondering this, we must understand that natural selection does not select for any traits. In fact, it selects against traits that are reproductively disadvantageous. Two big words--maybe I should clarify: suppose there are two possible traits in a critter, a red chest or a brown chest. Further suppose that, all other things being equal, those critters with a red chest have a much worse time hiding from predators and, therefore, tend to die younger (some even before they have a chance to reproduce at all) than those with a brown chest. Natural selection is at work here, selecting against red-chested critters, giving you more descendants of brown-chested critters, possibly until there are no more red chests in the critter population.

Going back to body hair, the question I find myself asking is, "why was it a disadvantage for our ancestors to have thicker body hair?" All other land mammals seem to get along just fine with more body hair in all environments. What was different about human ancestors? There is the possibility that the mutation that causes less body hair just never occurred in any other evolutionary line, but that seems unlikely to me. And why is it that we still have thick hair in certain places? What's special about an arm pit that the "less body hair" gene left that alone?

Along the same vein, why do women tend to have less body hair than men (even when they don't shave it off)? Clearly, some evolutionary force selected against women with much body hair. Nowadays, that could be seen because most men (in our culture, anyway) are more attracted to women with little body hair, but is that what started it all? If that was the selective factor, where did that attitude come from in the first place?

A similar question goes for head hair: "what was the disadvantage for not being able to grow long hair on the head?" Those who have had long hair can tell you the disadvantages of same: it takes a long time to dry; it gets tangled and is hard to maintain; it can get caught on things (which seems like a distinct disadvantage to a primitive ape to me); etc. Perhaps the two things are related; longer head hair had to come with less body hair for some reason (or vice versa).

Finally, why do men tend to grow facial hair, but women don't? (I'm speaking in generalities here, and not talking about a little "peach fuzz" on the upper lip.) What possible evolutionary factor could there have been to select against males with no facial hair, but against females with facial hair? Perhaps, again, we're looking at what specific mutations did or did not occur, but why affect males and females differently? Maybe it has something to do with the second X chromosome, seeing as the Y chromosome doesn't have as many genes on it. (I do know that this is the source of some male-female differences, such as pattern baldness, which is a recessive gene but occurs on the X chromosome and not on the Y. A woman with the gene might well have the dominant gene against pattern baldness on the other X chromosome. That's an oversimplification, I'm sure, but it's the basic idea as I understand it.)

I'm afraid I don't have the answers to any of these questions, but they have been occurring to me off and on for years. Please feel free to educate me if you know, or even share if you have a theory. I'd love to know what other people think, especially about the reduced body hair question.

Hey, not all my posts can be deep and meaningful. :-)

Random thoughts on bicycling, hockey, software development, and other nonsense

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

The Adjusted Plus-Minus

With the start of hockey season (though no NHL season just yet) upon us, my thoughts have turned towards the sport I love. This post may not be of much interest to those of you who aren't hockey fans (and maybe even to those who are but couldn't care less about stats). You have been warned.

The plus-minus; what it is

The plus-minus (or +/-) is relatively new in the hockey statistics world. It was first employed by the Montreal Canadiens in the 1950s and started being tracked by the NHL in 1968. That's over 40 years, but most fans had never heard of it until the last 15 or so (if ever). These days you hear it mentioned several times in most broadcasts, but what is it?

As with many sports, the most well known hockey statistics (goals and assists) are geared towards measuring a player's offensive ability. The plus-minus is intended to be a measure used for defensemen and defense-minded forwards. The statistic is calculated by taking the number of non-power play goals scored by the player's team (so even strength and shorthanded goals) while he/she is on the ice and subtracting the number of non-power play goals scored by the other team while he/she is on the ice. For example, suppose Roy was on the ice for 3 goals scored by his team, one of which was a power play goal. This gives him +2 (since the power play goal doesn't count).If the other team also scored 3 goals, none of them on the power play, then his plus-minus for the game is +2 - 3 = -1.

Once you get used to it, this is pretty straightforward. The idea is that a better defensive player will have a higher plus-minus since the other team will score less when he is on the ice and the offensive players on the team will likely score more since they can be confident that the defense is being taken care of.

What's wrong with the plus-minus

The plus-minus has a number of issues, but there two that I want to address here:

The first is that the plus-minus does not take into account the amount of time a player spends on the ice. A player that spends 20 minutes playing and earns a +1 is seen as contributing the same as a player who plays just 1 minute and also happens to earn a +1. This is not equitable.

The second (and, in my opinion, bigger) problem is that there is no baseline. Suppose Roy's team in the example above lost that game 14-3. Roy's -1 is actually quite good. On the other hand, if Roy's team won the game 14-3 then Roy's -1 is really bad. This becomes worse as you look at season or (shudder) career plus-minus. Someone who is very bad but plays for a very good team can have a season plus-minus that looks great, while someone who is very good but plays for a very bad team can have a plus-minus that looks horrible. (Take John Tavares, for example. His season plus-minus in 2011-12 was -6. That's on the minus side, so looks bad, but when you take into account that the Islanders were 26th in a league of 30 and that they were outscored by their opponents by 55 goals (251-196), his -6 is actually pretty decent. It's not great, but he's also a very offensively-minded player and it is 5th place on the team among players who played at least half the season.)

To make matters worse, stats pages and commentators compare plus-minus values between players on different teams as if that means anything. Is Chris Kunitz's +16 (5th among the Pittsburgh Penguins for players playing at least half the games in 2011-12) really better than John Tavares' -6? That's debatable since the Penguins outscored their opponents by 65 goals (273-218).

To make the plus-minus more comparable between teams, we need a baseline to work from. That's where my proposal for the adjusted plus-minus comes in.

Proposed solution: adjusted plus-minus

The goal behind the adjusted plus-minus is to create a statistic with a known baseline which is therefore comparable for players on different teams. The formula is below, but the idea is simple: adjust everyone's plus-minus so that a player that is neutral (in the sense of not directly affecting which team has more goals in the end) will have an adjusted plus-minus of 0. A positive adjusted plus-minus will show that the player is contributing to the team's success and a negative adjusted plus-minus will show that the player is not (or may, in fact, be contributing to the team's failure). The formula takes into account the player's time on the ice (TOI) as well as the overall performance of his team, thus addressing the two issues described above.

First, some notation:

EVTOI = the player's time on the ice when the teams are even strength. This includes 5 on 5, 4 on 4, 3 on 3, as well as times when one team has pulled the goalie in order to gain a one skater advantage. If either team is on a penalty kill then that time is not counted in the ESTOI.

EVTOT = the team's total time playing at even strength. (Obviously, this is the same for both teams in a single game, but not over the course of many games against differing opponents.)

TPM = the player's team's plus-minus. This is a total of all even strength and shorthanded goals scored by the players team minus all even strength and shorthanded goals scored by the opponent. In short, compute the traditional plus-minus for the entire team as if it was one person.

PPM = the player's traditional plus-minus.

Okay, here's the formula:

Once you get used to it, this is pretty straightforward. The idea is that a better defensive player will have a higher plus-minus since the other team will score less when he is on the ice and the offensive players on the team will likely score more since they can be confident that the defense is being taken care of.

What's wrong with the plus-minus

The plus-minus has a number of issues, but there two that I want to address here:

The first is that the plus-minus does not take into account the amount of time a player spends on the ice. A player that spends 20 minutes playing and earns a +1 is seen as contributing the same as a player who plays just 1 minute and also happens to earn a +1. This is not equitable.

The second (and, in my opinion, bigger) problem is that there is no baseline. Suppose Roy's team in the example above lost that game 14-3. Roy's -1 is actually quite good. On the other hand, if Roy's team won the game 14-3 then Roy's -1 is really bad. This becomes worse as you look at season or (shudder) career plus-minus. Someone who is very bad but plays for a very good team can have a season plus-minus that looks great, while someone who is very good but plays for a very bad team can have a plus-minus that looks horrible. (Take John Tavares, for example. His season plus-minus in 2011-12 was -6. That's on the minus side, so looks bad, but when you take into account that the Islanders were 26th in a league of 30 and that they were outscored by their opponents by 55 goals (251-196), his -6 is actually pretty decent. It's not great, but he's also a very offensively-minded player and it is 5th place on the team among players who played at least half the season.)

To make matters worse, stats pages and commentators compare plus-minus values between players on different teams as if that means anything. Is Chris Kunitz's +16 (5th among the Pittsburgh Penguins for players playing at least half the games in 2011-12) really better than John Tavares' -6? That's debatable since the Penguins outscored their opponents by 65 goals (273-218).

To make the plus-minus more comparable between teams, we need a baseline to work from. That's where my proposal for the adjusted plus-minus comes in.

Proposed solution: adjusted plus-minus

The goal behind the adjusted plus-minus is to create a statistic with a known baseline which is therefore comparable for players on different teams. The formula is below, but the idea is simple: adjust everyone's plus-minus so that a player that is neutral (in the sense of not directly affecting which team has more goals in the end) will have an adjusted plus-minus of 0. A positive adjusted plus-minus will show that the player is contributing to the team's success and a negative adjusted plus-minus will show that the player is not (or may, in fact, be contributing to the team's failure). The formula takes into account the player's time on the ice (TOI) as well as the overall performance of his team, thus addressing the two issues described above.

First, some notation:

EVTOI = the player's time on the ice when the teams are even strength. This includes 5 on 5, 4 on 4, 3 on 3, as well as times when one team has pulled the goalie in order to gain a one skater advantage. If either team is on a penalty kill then that time is not counted in the ESTOI.

EVTOT = the team's total time playing at even strength. (Obviously, this is the same for both teams in a single game, but not over the course of many games against differing opponents.)

TPM = the player's team's plus-minus. This is a total of all even strength and shorthanded goals scored by the players team minus all even strength and shorthanded goals scored by the opponent. In short, compute the traditional plus-minus for the entire team as if it was one person.

PPM = the player's traditional plus-minus.

Okay, here's the formula:

Adjusted plus-minus = PPM - (TPM * EVTOI/EVTOT)

The logic is as follows:

EVTOI/EVTOT gives you the fraction of the team's even strength time during which the player was playing. Shorthanded goals for or against wind up acting as a bonus or penalty for the player, but power play goals either way do not affect them, so that time is not included in the ratio. In this way, the time that the player spends on the ice is taken into account in the statistic.

Multiplying EVTOI/EVTOT by TPM gives you the player's "expected" plus-minus. This is the plus-minus that would be earned by a player who is neutral in the sense described above. This is very likely to be a fractional amount; I've been rounding to two decimal places in my personal calculations, but any number of places could be chosen.

Subtracting the expected plus-minus from the actual plus-minus gives a statistic with a baseline of zero. A neutral player would be "even" (an adjusted plus-minus of 0), no matter how good or bad his/her team was.

Example with full statistics available:

Let's get some more information about Roy's game. The actual score for the game was 9-4, Roy's team lost, scoring once on the power play and giving up two power play goals against. The team's total plus-minus, then is TPM = 3 - 7 = -4. (3 because they scored 3 non-power play goals and 7 because they gave up 7 non-power play goals).

During the game, Roy played a total of 17:30 of ice time: 0:45 on the penalty kill, 1:15 on the power play, and the rest at even strength. That makes Roy's EVTOI = 15:30 (17:30 - 0:45 - 1:15).

During the 60:00 game, the team spent 4:30 shorthanded and 5:15 on the power play. Thus the teams even strength time is EVTOT = 50:15 and Roy's EVTOI/EVTOT = 15:30/50:15 = 0.31 (approximately).

Multiply that by the TPM and you get 0.31 * -4 = -1.24. This is Roy's expected plus-minus. His adjusted plus-minus, therefore is -1 - (-1.24) = +0.24. Roy was actually a little bit of a help to his team in this game, in spite of the -1 rating.

How to adjust for rec league:

Of course, most of us don't have that detailed TOI data to refer to. In my rec league, I've simplified the calculation to simply take the approximate fraction of the game I play based on the number of people playing my position. If I'm one of three centers, for example, then I make the fraction 1/3. If I'm one of 5 defensemen, I make it 2/5 (two defensemen on the ice at any time divided by 5 total). Other than that, I compute it just as described above.

Update 9/24/2012: As an example of what a difference it can make, I offer my own stats from the SCHL for summer 2012. That was a rough session for my team; we went winless and were completely blown out multiple times. My plus-minus for the summer was -21. My adjusted plus-minus was -0.70. I was still on the minus side, which doesn't please me, but at least it shows that I wasn't a complete drag on the team, which a -21 might seem to imply at first.

EVTOI/EVTOT gives you the fraction of the team's even strength time during which the player was playing. Shorthanded goals for or against wind up acting as a bonus or penalty for the player, but power play goals either way do not affect them, so that time is not included in the ratio. In this way, the time that the player spends on the ice is taken into account in the statistic.

Multiplying EVTOI/EVTOT by TPM gives you the player's "expected" plus-minus. This is the plus-minus that would be earned by a player who is neutral in the sense described above. This is very likely to be a fractional amount; I've been rounding to two decimal places in my personal calculations, but any number of places could be chosen.

Subtracting the expected plus-minus from the actual plus-minus gives a statistic with a baseline of zero. A neutral player would be "even" (an adjusted plus-minus of 0), no matter how good or bad his/her team was.

Example with full statistics available:

Let's get some more information about Roy's game. The actual score for the game was 9-4, Roy's team lost, scoring once on the power play and giving up two power play goals against. The team's total plus-minus, then is TPM = 3 - 7 = -4. (3 because they scored 3 non-power play goals and 7 because they gave up 7 non-power play goals).

During the game, Roy played a total of 17:30 of ice time: 0:45 on the penalty kill, 1:15 on the power play, and the rest at even strength. That makes Roy's EVTOI = 15:30 (17:30 - 0:45 - 1:15).

During the 60:00 game, the team spent 4:30 shorthanded and 5:15 on the power play. Thus the teams even strength time is EVTOT = 50:15 and Roy's EVTOI/EVTOT = 15:30/50:15 = 0.31 (approximately).

Multiply that by the TPM and you get 0.31 * -4 = -1.24. This is Roy's expected plus-minus. His adjusted plus-minus, therefore is -1 - (-1.24) = +0.24. Roy was actually a little bit of a help to his team in this game, in spite of the -1 rating.

How to adjust for rec league:

Of course, most of us don't have that detailed TOI data to refer to. In my rec league, I've simplified the calculation to simply take the approximate fraction of the game I play based on the number of people playing my position. If I'm one of three centers, for example, then I make the fraction 1/3. If I'm one of 5 defensemen, I make it 2/5 (two defensemen on the ice at any time divided by 5 total). Other than that, I compute it just as described above.

Update 9/24/2012: As an example of what a difference it can make, I offer my own stats from the SCHL for summer 2012. That was a rough session for my team; we went winless and were completely blown out multiple times. My plus-minus for the summer was -21. My adjusted plus-minus was -0.70. I was still on the minus side, which doesn't please me, but at least it shows that I wasn't a complete drag on the team, which a -21 might seem to imply at first.

Please feel free to ask any questions and/or offer any critiques of this proposed statistic. I've been using it for myself for years, but I'd like to know what other people think.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

Dear FedEx

The following is the actual text (copied and pasted) of an email I sent to FedEx.

Dear FedEx,

I regularly ride my bicycle from my home in New Haven, CT to my work in Wallingford, CT. My usual route takes me past the FedEx Ground location at 29 Toelles Rd in Wallingford. That particular part of my route is not the best for a bicycle and I'm frequently annoyed (and occasionally frightened) by the many commuters driving along that road in the morning. One thing I don't have to worry about, however, is the drivers of the many FedEx vehicles I see. The drivers are always polite and respectful of my right to be on the road and never do anything that I feel places me in danger in their presence.

Nearby Mt Carmel Ave/Kings Hwy is the only direct route between that part of Wallingford and both the bike trail that half of my commute is along and a major north-south artery used frequently by your drivers. It is a narrow, winding, two lane road with no shoulders which climbs up and over a small ridge just south of Sleeping Giant. I frequently encounter FedEx delivery vans along that road. Even on that cramped road, FedEx drivers have been the most courteous and safest drivers I have encountered. They never pass me as I'm attempting to finish a steep climb with no shoulder and never pass when approaching a corner, something that other vehicles do along there almost every day. I feel bad sometimes because I do slow them for up to a minute or so as they wait for a safe place to pass, but I want them and you to know that I appreciate their courtesy and that they always give me plenty of room when passing.

Connecticut is not the home of the country's best, most courteous, or safest drivers, but the FedEx drivers I have encountered have always been respectful, courteous, and safe around me on my bicycle and for that I am grateful. I want others to know how much I appreciate your drivers, so a copy of this email will be posted to my blog (http://twocatsonabike.blogspot.com).

Thank you,

Scott MacDonald

Dear FedEx,

I regularly ride my bicycle from my home in New Haven, CT to my work in Wallingford, CT. My usual route takes me past the FedEx Ground location at 29 Toelles Rd in Wallingford. That particular part of my route is not the best for a bicycle and I'm frequently annoyed (and occasionally frightened) by the many commuters driving along that road in the morning. One thing I don't have to worry about, however, is the drivers of the many FedEx vehicles I see. The drivers are always polite and respectful of my right to be on the road and never do anything that I feel places me in danger in their presence.

Nearby Mt Carmel Ave/Kings Hwy is the only direct route between that part of Wallingford and both the bike trail that half of my commute is along and a major north-south artery used frequently by your drivers. It is a narrow, winding, two lane road with no shoulders which climbs up and over a small ridge just south of Sleeping Giant. I frequently encounter FedEx delivery vans along that road. Even on that cramped road, FedEx drivers have been the most courteous and safest drivers I have encountered. They never pass me as I'm attempting to finish a steep climb with no shoulder and never pass when approaching a corner, something that other vehicles do along there almost every day. I feel bad sometimes because I do slow them for up to a minute or so as they wait for a safe place to pass, but I want them and you to know that I appreciate their courtesy and that they always give me plenty of room when passing.

Connecticut is not the home of the country's best, most courteous, or safest drivers, but the FedEx drivers I have encountered have always been respectful, courteous, and safe around me on my bicycle and for that I am grateful. I want others to know how much I appreciate your drivers, so a copy of this email will be posted to my blog (http://twocatsonabike.blogspot.com).

Thank you,

Scott MacDonald

Saturday, August 18, 2012

A Driving Primer for Connecticut Drivers, Part 3

This primer is presented somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but it is inspired by

the actual activity I've seen on the roads since moving to Connecticut.

To be fair, it may just be the greater New Haven drivers that really

need this primer, as I hear that even Massachusetts drivers think New

Haven area drivers are terrible. One legal-ish note: none of the images

used here are mine. Click on an image to see where I've linked to it

from and any copyright information that may be included.

Part 1 of this driving primer focused on the confusing lines in the road that run parallel to the road itself. Part 2 focused on those weird color-changing "traffic" lights and two types of lines that run across the road: stop lines and crosswalks.

Part 3: Stop Signs and Unmarked Intersections

If you've driven much at all then you're probably come across one of those weird 8-sided red signs with the enigmatic message "STOP" written on them in white letters. Though many feel that these signs are ambiguous at best, we'll unravel the mystery of what they mean here. We will also tackle the difficult problem of what to do when two streets cross each other but there are no "traffic" lights and none of these "STOP" signs.

Part 1 of this driving primer focused on the confusing lines in the road that run parallel to the road itself. Part 2 focused on those weird color-changing "traffic" lights and two types of lines that run across the road: stop lines and crosswalks.

Part 3: Stop Signs and Unmarked Intersections

If you've driven much at all then you're probably come across one of those weird 8-sided red signs with the enigmatic message "STOP" written on them in white letters. Though many feel that these signs are ambiguous at best, we'll unravel the mystery of what they mean here. We will also tackle the difficult problem of what to do when two streets cross each other but there are no "traffic" lights and none of these "STOP" signs.

- Stop signs "STOP" signs (or simply, stop signs) seem to be everywhere. To many drivers (and to even more bicyclists, but that's another post), they simply have no meaning and can be ignored. Here's a typical stop sign in the wild:

To begin to unravel the mystery of what to do when confronted with one of these signs, I started by trying to find out what the acronym "S.T.O.P." stood for. Much to my surprise, I discovered that it is not an acronym, but an actual English word! The word has many definitions, but the one that seems the most relevant in a driving situation is this: "To cease moving, progressing, acting, or operating; come to a halt." This makes it clear what one must do when confronted by a stop sign; one must come to a halt. But where? Most stop signs come paired with a stop line (see part 2 of this primer).

The stop line in the above image is a bit worn, but it's there. When a stop line is provided, treat it just like a stop line at a traffic light: stop there. Not 15 feet before you reach it. Not after your car has crossed it (and therefore entered the intersection). Stop so that the front of your car is at the stop line and the rest of the car has not yet crossed it. If there is no stop line then stop before the front of your car enters the intersection. (I placed emphasis on the word "before" because so many people seem to miss it.)

Once you have stopped your vehicle, it is not necessary to remain stopped indefinitely. Instead, carefully look for the following: (a) other vehicles approaching the intersection whose route will intersect yours and who do not themselves have a stop sign and (b) pedestrians. As much as I joke about things being difficult, this looking for pedestrians bit is extremely important, yet seems to be missed by many, many people. I don't know how many times I've seen a pedestrian hit or nearly hit by a car because the driver was so busy peering around the pedestrian for traffic that they never even saw the pedestrian.

Pedestrians have the right of way at intersections whether there's a crosswalk painted there or not. If someone is crossing the street, don't just stop right in front of them and figure they'll go around you. Stop far enough back that they can safely pass in front of your vehicle, let them do so, then move forward to where you can see oncoming traffic and stop again to look for traffic. (True story: I was crossing a street when a woman pulled up to the intersection, stopped before entering the crosswalk, looked me in the eye, then pulled forward inches in front of me to look for traffic and stopped. She was so close that I lost my balance trying to dodge around the back of her car and accidentally hit it with my hand as she started to drive off. She stopped (in front of oncoming traffic), rolled down the passenger window, and yelled, "That's how people get shot!" By getting cut off by a rude driver and losing their balance? Whatever.) - All way stops Many people are honestly confused about what to do with they approach an all way stop (frequently referred to as a 4 way stop, since most intersections have traffic traveling in four directions).

All joking aside, all way stops are clearly very confusing for people, so here are the rules on how to handle an all way stop.- First, come to a stop just as you would with any other stop sign.

- Look for traffic (and pedestrians!); if there is no other traffic then proceed on your way.

- If another vehicle arrived at the intersection before you then they have the right to go first, so you must wait until they have gone before you go.

- If two (or more) vehicles arrive at the intersection at the same time, then right-of-way is determined as follows:

- The vehicle immediately to your right has right-of-way over you. You must wait until that vehicle has gone before you go.

- It follows from the above that you have right-of-way over the vehicle to your left. Make eye contact with the other driver (if possible) and make sure that they are yielding that right-of-way to you, then proceed if it is otherwise safe.

- If the other vehicle is coming the other direction then right-of-way only matters if one or both of you is turning left (or otherwise crossing the other's path). In that case, any vehicle going straight or turning right has the right-of-way and the left turner must yield.

- Sometimes you come to an all way stop to find that there are lines of vehicles waiting in all directions. This is a situation in which many drivers are confused and don't know what to do. The important thing here is to take turns. To determine who goes next, figure arrival time at the intersection to be when each vehicle reaches the front of the line and use the right-of-way rules described above.

One final important comment related to all way stops: if you come to a traffic light that is either completely nonfunctional (dark) or which is flashing red in all directions then that traffic light is an all way stop. These can be difficult to navigate if it is a large intersection with multiple lanes going in each direction. Here, again, turns should be taken, with all vehicles traveling in a certain direction going at the same time. One vehicle from each lane should go with each "turn". There should not be multiple vehicles from the same lane going through the intersection at the same time, I don't care how frustrated the drivers are or how long they've been waiting; others have also been waiting and are probably just as frustrated. You're all in that situation together, so cooperate to get through it safely. - Unmarked intersections Also known as "uncontrolled" intersections, these are intersections with no stop lights or traffic control signage whatsoever.

Having learned the rules for all way stops above, unmarked intersections should be a breeze: the only difference is that you don't have to stop before going through the intersection if there is no other vehicle with right-of-way over you. That emphasized part is the part that a lot of people don't seem to realize. You do need to slow down enough when approaching an unmarked intersection to determine whether or not (a) you have the right-of-way and (b) if it is, in fact, safe to go through the intersection. Not checking for both of these things leads to this:

This accident occurred in an unmarked intersection. None of the three drivers involved was paying attention to cross traffic. Luckily, no one was seriously hurt, but the drivers of the Cavalier and Jeep got free trips to the hospital and the driver of the truck got to explain to his boss why he totaled a company car when he could have prevented the whole accident just by glancing to his right.

There is one important situation in which an unmarked intersection does not have the same right-of-way rules as an all way stop. This is at a "T" intersection (i.e., one of the roads ends at the intersection while the other continues on).

In this situation, the car on the road that ends (the red car above) is required to yield to all vehicles on the road that continues through (the blue and yellow cars above).

Monday, July 30, 2012

Silly method calls

I know my millions of readers are hanging on the edges of their seats waiting for the third part of the driving primer, but I encountered something at work today that I just have to comment on.

I was looking through some code and found something like the following. (I can't give the real code since that belongs to the company.)

Further down is the definition of the method being called

In other words, the unnamed engineer who wrote this code chose to use three lines to write a method PLUS a line to call the method when the method consisted of a single line in the first place. Why not just put

This particular software was originally written in C++ and was translated to Java by C++ programmers who had taught themselves Java. One of the principles by which Java programmers tend to work is to write "self-documenting" code. This means that instead of writing a bunch of complex code in the middle of a method in order to accomplish something, put that complex code in a method and give the method a name that describes what the code is supposed to do. Some people who are making a transition to using Java interpret this as meaning that you should always do this, even if there is only one line of code to go in the method. My guess is that this is exactly what the unnamed engineer was thinking.

Look at the code in the example above. Is

I was looking through some code and found something like the following. (I can't give the real code since that belongs to the company.)

typeComboBoxEnable(true);Further down is the definition of the method being called

private void typeComboBoxEnable(boolean e) {

typeComboBox.enable(e);

}In other words, the unnamed engineer who wrote this code chose to use three lines to write a method PLUS a line to call the method when the method consisted of a single line in the first place. Why not just put

typeComboBox.enable(true) in place of the method call? There is no good reason, really. Since the person who wrote the code is no longer with the company, I can't even ask him what the heck he was thinking; I can only guess. So, of course, that's exactly what I'm going to do. :-)This particular software was originally written in C++ and was translated to Java by C++ programmers who had taught themselves Java. One of the principles by which Java programmers tend to work is to write "self-documenting" code. This means that instead of writing a bunch of complex code in the middle of a method in order to accomplish something, put that complex code in a method and give the method a name that describes what the code is supposed to do. Some people who are making a transition to using Java interpret this as meaning that you should always do this, even if there is only one line of code to go in the method. My guess is that this is exactly what the unnamed engineer was thinking.

Look at the code in the example above. Is

typeComboBoxEnable(true) more clear than typeComboBox.enable(true)? I would argue that it is not. For one thing, they contain exactly the same description of what is being done; there is no benefit to documentation to call the method instead, and by doing it that way, more code had to be written. This is a poor design and should be avoided.

Thursday, July 26, 2012

A Driving Primer for Connecticut Drivers, Part 2

This primer is presented somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but it is inspired by

the actual activity I've seen on the roads since moving to Connecticut.

To be fair, it may just be the greater New Haven drivers that really

need this primer, as I hear that even Massachusetts drivers think New

Haven area drivers are terrible. One legal-ish note: none of the images

used here are mine. Click on an image to see where I've linked to it

from and any copyright information that may be included.

Part 1 of this driving primer focused on the confusing lines in the road that run parallel to the road itself.

Part 2: Traffic Lights, Stop Lines, and Crosswalks

One particularly difficult item that drivers must deal with during almost any drive is what to do at a traffic light or intersection. The rules seem vague or pointless, but they really are very specific. In this part of our driving primer, we uncover just exactly what these rules tell you to do in nearly any situation.

Part 1 of this driving primer focused on the confusing lines in the road that run parallel to the road itself.

Part 2: Traffic Lights, Stop Lines, and Crosswalks

One particularly difficult item that drivers must deal with during almost any drive is what to do at a traffic light or intersection. The rules seem vague or pointless, but they really are very specific. In this part of our driving primer, we uncover just exactly what these rules tell you to do in nearly any situation.

- Traffic lights We will focus on how traffic lights work in the United States, since this primer is aimed at Connecticut drivers, and Connecticut spends the vast majority of its time in the U.S.A. Traffic lights in other countries sometimes behave differently (even as nearby as Canada, where there is a flashing green), but covering everything would be confusing.

Traffic lights in the United States may typically be found in one of three states, as shown below (shamelessly clipped from a Wikipedia article which is, ironically, about how traffic lights work in the United Kingdom):

Note the explanation of each of the figures.

Figure 1's explanation says that a red light means stop. This means that if the traffic light looks like figure 1 before you and your vehicle enter the intersection then you must stop your vehicle and wait for it to look like figure 2 before going through. It does not mean that 4 or 5 more vehicles should go through the intersection even though the right light is showing, in spite of what many drivers in the New Haven area clearly believe. This is one of those places where the rule is actually very clear (you must stop and wait) but that common interpretation (you might stop, but if you're in one of the first "few" cars then it's okay to go through) makes it seem more confusing than it really is.

There is one situation where you do not need to wait for the light to resemble figure 2 before proceeding: the "right turn on red", or "free right turn". The rule is still very clear about this, however. You must stop before making the turn. You stop your vehicle and carefully look to make sure no traffic is coming towards you before making the turn. Some motorists seem to think that simply coasting for a moment and then turning without looking for oncoming traffic is okay. It is not. The main rule is really very simple: if the red light is glowing then you must stop your vehicle. Important note: The presence of a sign that says "NO TURN ON RED" means that you are not allowed to perform a "right turn on red" maneuver. In that case, you must stop your vehicle and wait for the green light to glow before making your turn.

I now bring your attention to figure 3; the yellow (or "amber") light glowing. This state occurs just after figure 2 and just before figure 1. It is a warning to you that the red light is about to start glowing, so you should prepare to stop. In Connecticut, it appears that many motorists are not aware that this state is any different from the state shown in figure 2. In a sense it isn't: if you're already passing through the intersection (or just entering it) when the amber light comes on then you may continue through. Otherwise, you should prepare to stop since the red light will come on shortly. (Side note: in many states, including my native Washington (the state, not D.C.), drivers seem to believe that figure 3 means "go really, really fast so you don't have to stop when the red light comes on". It turns out that this is also incorrect as, if anything, you should slow down when the amber light is lit, not speed up.) - Stop lines and crosswalks

- Stop Lines The solid white lines that go halfway across the

road on each side of this intersection (see the image below) are called stop lines. When

approaching the intersection, if the light facing you is showing red (see figure 1, above),

then stop your vehicle before crossing this line. Your vehicle should not be across the line, even part way, when you come to a stop. What you should definitely not do is stop with the stop line behind

you. If you have done that then you are (by definition) in the intersection.

Sometimes, the stop lines seem to be set way back from the intersection itself. Take, for example, the stop line on the right in the image above. That stop line is so far back for a very good reason: buses and other large vehicles traveling north (upwards in the image) frequently turn right at that intersection. If you don't stop before your vehicle crosses that line then they will be unable to turn the corner without hitting your vehicle (which the bus drivers in Connecticut have no problems with doing). If you see a stop line that seems unreasonably far back from the intersection then it is back there for a reason. Stop there anyway. - Crosswalks Crosswalks are places where people walking, jogging, or otherwise moving themselves along with their feet (we'll call these people "pedestrians") are supposed to be able to cross the street safely and without vehicles in their way. A crosswalk can be identified by two white lines several feet apart perpendicular to the road and all the way across the road. In the image above, there are two crosswalks: one on the road coming in from the right and one at the bottom of the intersection. Note how these crosswalks are lined up with the sidewalks for the convenience of the pedestrians (who should be using the sidewalks). Note also that the crosswalks are beyond the stop lines. In other words, if you stop at the stop line then you are in no way blocking the crosswalk with your vehicle. You should never stop your vehicle in a crosswalk (unless not doing so would cause an accident, of course). The crosswalk is part of the intersection, so stopping in the crosswalk is just like stopping right in the middle of the intersection: it's rude, dangerous, and illegal.

Little known fact: In spite of how they are spaced, the point of the lines for crosswalks is not to stop with your front wheels on one line and your rear wheels on the other. While this is a fun and exciting game to play in the privacy of your own backyard, it is dangerous, rude, and illegal to do so on public roadways.

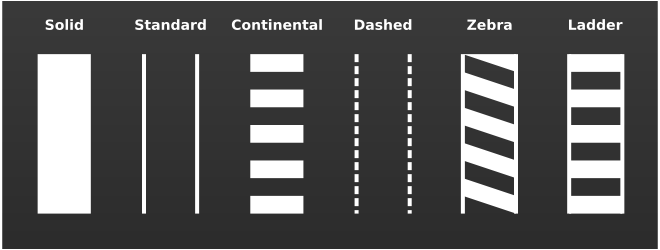

Crosswalks can be marked in many different ways. I focused on the "standard" style of crosswalk above, but crosswalks can actually be marked in many different ways, as shown in the image below:

Any of these can be used to indicate a crosswalk, so watch out for any of them.

One final important note about crosswalks: they don't always occur at intersections. When you encounter a crosswalk in a location with no intersection (or special traffic light), look before driving through the crosswalk to see if any pedestrians are either (a) currently in the crosswalk or (b) at the edge of the road and appearing to wish to use the crosswalk. If either one of these conditions is met then stop your vehicle before beginning to go through the crosswalk and wait for the pedestrian(s) to finish using the crosswalk before continuing. The white car in the picture below is doing it wrong. (The pedestrian in this picture is a policeman, by the way. Just something to think about.)

The cars in this picture, on the other hand, are doing it right at the very same crosswalk. (Note that this crosswalk is not at an intersection.)

Friday, July 20, 2012

A Driving Primer for Connecticut Drivers, Part 1

This primer is presented somewhat tongue-in-cheek, but it is inspired by the actual activity I've seen on the roads since moving to Connecticut. To be fair, it may just be the greater New Haven drivers that really need this primer, as I hear that even Massachusetts drivers think New Haven area drivers are terrible. One legal-ish note: none of the images used here are mine. Click on an image to see where I've linked to it from and any copyright information that may be included.

Part 1: What are those yellow and white lines along the road for?

The funny lines you see on the road are there for an actual reason and not just for decoration, believe it or not. After some really extensive research, I've found out what many of them mean. For this first part, we take a look at those lines that are parallel to the direction of travel on the road. For some reason, they come in both yellow and white; this is one of the things that is most baffling about the lines on the road.

Part 1: What are those yellow and white lines along the road for?

The funny lines you see on the road are there for an actual reason and not just for decoration, believe it or not. After some really extensive research, I've found out what many of them mean. For this first part, we take a look at those lines that are parallel to the direction of travel on the road. For some reason, they come in both yellow and white; this is one of the things that is most baffling about the lines on the road.

-

Yellow lines. It turns out that the yellow lines are supposed to be a divider between traffic traveling in each direction. In the U.S. (and many other countries), you are supposed to keep the yellow line on the left side of your car at all times, even when going around corners like those shown above! Apparently, you're not supposed to drive straight through a section of road like the one above, touching your tires to the inside curb on each curve. This is true even if one of the yellow lines is missing or dashed instead of solid. One clarification: when keeping the line to the left of your car, you are supposed to leave some space between your car and the yellow line. You are not supposed to drive with your left tires on or slightly across the line.

- White lines. There are apparently two different types of white lines which are parallel to the road (we'll get to lines across the road in the next part); some designate a thing called "lanes" and others mark the edge of the road. (Both of the white lines in the above image are of the "edge of the road" variety--see below.)

- "Lanes" are difficult to explain, so I'll start with an image:

Note how the cars in this image are in straight rows with those dashed white lines in between the rows. The area between the rows that the cars are driving in are called "lanes". My research indicates that when driving on a road with multiple lanes, you are supposed to choose a lane (always remembering to keep the yellow line to your left, even if it isn't directly bordering your lane) and stay in it. This means not drifting onto (or over) the line between the lanes and back again. It also means not driving with one of the divider lines under your tires or car!! Apparently, drivers in a lot of places have mastered this difficult task and rarely cross the lines between the lanes inadvertently.

Once you have chosen a lane, you are not stuck in it forever. You can, when needed, execute a difficult maneuver known as a "lane change". It's accomplished following a few simple steps:

(1) Wait until there are no cars next to you or immediately behind or in front of you in the lane you wish to move into. You can determine when this is so by looking out the windows of your car (this may require putting your phone down) and, for checking behind the car, by looking in the mirrors.

(2) Turn on the turn signal on the side of your car that the lane you wish to move into is on. Note that at this point, you have not yet begun to move into the other lane.

(3) Double-check to make sure that there is no one in the space that you want to move into in the new lane. This must be done by turning your head and looking, do not use the mirrors for this, as they have "blind" spots and there may be traffic lurking in them.

(4) Assuming that this is no other vehicle in the space you want to move into, move into that space quickly (over the course of 2 or 3 seconds) and smoothly. Do not take 3 minutes to complete a lane change. This is considered simply drifting across the lane lines, which I explained above is not something you're supposed to do.

One last thing about lane lines: sometimes, they appear in intersections, such as this one in Hamden, CT.

These are to guide you through the intersection. If turning left through the intersection in a direction indicated by one of these dashed lines, remain on the same side of that line as you were when you started all the way through the intersection, as illustrated below.

Notice how the black SUV heading south stays to the left of the guide line (red arrow), but the white car heading east must stay to the right of the guide line (blue arrow). The white car's path is very important because there may be, unbeknownst to the driver of the white vehicle, another car also turning from the lane just to the left of it. If the white car crosses the guide line then it may strike the car on its left. This is bad. - "Edge of the road" lines, also known in some parts of the country as "fog" lines or "shoulder" lines mark the edge of the roadway. In the normal course of driving, your tires should never cross one of these lines. There are two exceptions: (1) pulling over to park at the side of the road and (2) turning into a driveway. In both of these cases, you are expected to use your turn signal to warn other drivers that you are about to do something "unexpected". (I put the word in quotation marks because you know you are about to do it, so it's not really unexpected, but remember that, unlike you, the other drivers are pretty self-centered and clueless, so they don't know what you're going to do and you have to clue them in.)

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Five Bicycling Safety Myths Dispelled

I wouldn't be fulfilling my stated purpose for this blog without discussion of bicycle safety, both from the bicyclist's viewpoint and from the viewpoint of drivers who are sharing the rode with cyclists. This entry focuses on the bicyclist and the many things that people do when riding because they think it's safe or legal when, in fact, it is unsafe or illegal (frequently both).

- Myth: It is safer to ride on the sidewalk than on the street.

Fact: A cyclist on a sidewalk is almost twice as likely to get hit by a car than one riding in the street. (source: BicyclingLife.com--see table 5; note also in table 4 how much each risk goes up when riding on the sidewalk. Also, while not stating how much more likely to get hit on the sidewalk than the street, BicycleSafe.com points out many scenarios in which the best way to avoid a certain type of accident is to not be riding on the sidewalk in the first place.)

Why: Most adult cyclists are also drivers, so I ask you to look at it from the driver's point of view for a moment; when you are pulling out of a driveway, are you expecting a bicycle on the sidewalk or are you looking for vehicle traffic out in the street? Most of us will look briefly for pedestrians on the sidewalk, but we are not expecting faster moving bicycles, so we don't look far enough up and down the sidewalk to see them. The driveway out of my building is blind on the right for any vehicle shorter than a large SUV thanks to a tall hedge. I always stop at the edge of the sidewalk and peer over and through the hedge to look for pedestrians, but I would probably not be able to see a bicycle that way--most bikes are moving too quickly for a person's eyes to focus on them quickly through gaps in the hedge. Besides, I've watched many cars come out of that driveway without even pausing at the sidewalk. A pedestrian might be able to stop instantly and/or jump back out of the way of a car at that point, but a bicycle is far less maneuverable.

The other consideration here is that in many places, riding on the sidewalk is illegal. (I admit that until today I thought that was the case everywhere, but while doing my research, I discovered otherwise.) Those communities where it is not expressly illegal to ride on the sidewalk are unlikely to endorse it, either, as it can open them up to lawsuits.

Legal where you are or not, riding on a sidewalk is dangerous. If you insist on doing so anyway, please follow the http://www.commutebybike.com/2008/07/09/top-5-rules-for-riding-on-the-sidewalk/ as presented by CommuteByBike.com. - Myth: It is safer to ride facing traffic so you can see cars coming (and they won't hit you from behind).

Fact: You are nearly four times as likely to get hit by a car when riding facing traffic than when riding with traffic. (source: BicyclingLife.com--see table 4) Nearly a quarter of all car-bicycle collisions are the result of the bicycle riding against traffic. (Before arguing that this shows it's more dangerous to ride with the traffic, keep in mind that only 8% of cyclists ride against traffic, so those 8% of the cyclists are causing 25% of the accidents.)

Why: Once again, I ask you to put yourself in the driver's seat of a car pulling onto a road from a driveway or side road. If you're turning right, are you looking for traffic coming from your right? If you said 'yes' then you are either a very strange person or a liar. Most people will glance to the right to make sure the road is clear before turning (but while already moving, and much too late to stop for a bicycle riding at them), but up to that point, they look to where the traffic is expected to be coming from: the left. If you're riding the wrong way down a one way street then even someone turning left isn't going to look your way since they don't expect traffic to be coming from that direction.

You may think that you're okay because you are always very careful to make sure that drivers pulling onto the road see you before you cross in front of them. That's very prudent, but they are not the only danger as a result of riding the wrong direction. I witnessed a very near car-bicycle accident a couple of weeks ago in which the cyclist was riding on the left side of a two way street and the driver was traveling in the same direction on the right side of the street. How did they nearly collide? The driver waited until there was a break in oncoming traffic and made a perfectly legal left turn into a driveway. The cyclist just happened to be just about to go across that driveway at the time; there was no reason why the driver should have expected traffic coming from behind her to be an issue as she made that turn. In this case, the cyclist was barely able to go around behind the car, but many cyclists in that situation are not so lucky.

Many people will ride facing traffic to avoid getting hit from behind by a car. The fact is that this is by far the least likely car-bike collision to occur (only 3.8% of collisions are of this type source: BicyclingLife.com), and when it does, it is almost always at night and the bicycle has no lights or reflectors and the rider is not wearing any reflective gear. Don't ride at night with no lights or reflective gear and you are almost certain never to be hit from behind by a car.

One final thought that I confess hadn't occurred to me before today but that I found on BicycleSafe.com while doing my research. Suppose you are riding 10 mph and the traffic is moving at 30 mph. If a car hits you from behind then the speed of impact is 30 - 10 = 20 mph. If you are facing traffic, so hit a car head on, then the speed of impact is 30 + 10 = 40 mph. That's twice as fast. So even if you did get hit from behind (exceedingly unlikely though it is), you're still better off.

Bicycling with traffic while following the rules of the road (see below) is, in fact, safer than many other common activities, including driving a car. A list of activities and the likelihood of an accident while participating in each is given in BicyclingLife's Modern Bicycle Myths. - Myth: Bicycles don't need to stop at red lights or stop signs (or are allowed to cross on "all way walk" signals).

Fact: Bicycles are required to follow the same rules of the road as any motor vehicle and then some. (source: livestrong.com)

Why: Bicycles are vehicles and, as such, are required to follow the rules of the road. This is not only the law, but following the rules of the road makes your behavior predictable and, therefore, safer for you and the motorists around you. As far as "all way walk" signals go; they are intended to allow pedestrians to walk across the street safely. Bicyclists are not pedestrians unless they walk their bicycle--if you walk across then you can go with a walk signal. Otherwise, you wait with the cars. - Myth: Bicycles must keep as far right as possible at all times when traveling on a road.

Fact: Bicycles must keep right as long as it is safe to do so and doing so doesn't violate other rules of the road.

Why: Requiring bicyclists to stay as far right as possible would require them to ride through all kinds of crap on the road, including broken glass, collected silt, fallen tree branches, and parked cars. Obviously, a bike must be allowed to move left to get around these obstacles.

Speaking of parked cars, when passing them, a cyclist should not ride as close to them as possible. This is remarkably dangerous, as you cannot always see if someone is in one of those parked cars and may throw their door open without warning. Always maintain a safe distance from parked cars; this is generally at least 3 feet (which, incidentally, is the amount of space that cars are required to give a bicycle when passing them; but that's a topic for another day).

Another reason for not staying right is following traffic laws. If I am turning left at an intersection where a left turn lane is provided, I must use said left turn lane. It is not only the legal way to do it; it is also the safest. If I'm out in the left turn lane then everyone knows I'm turning left--not even a crazy bicyclist would accidentally move into the left turn lane when planning to go straight, would they? Likewise, if there is a right turn lane and I plan to go straight, it would very dangerous for me to keep to the right of the turn lane and try to go straight through the intersection (see below). It's much safer to move out into a lane where the traffic is expected to go straight. - Myth: It is okay for a bicycle to pass cars on the right when they are stopped at a traffic light or stop sign.

Fact: This is a good way to get yourself killed when a car suddenly pulls over or turns right.

Why: One last time, I ask you to put yourself in the driver's seat. You're planning on turning right, so you're waiting for break in cross traffic (or a green light) to do so. Where is your attention? It is on the cross traffic and/or the traffic signal. It is not on the shoulder to your right. When you get a break or green light, you are going to look down the road you're turning onto and make the turn; you're still not expecting traffic to be passing you on your right at this point.

This behavior is one of the scariest that I see in otherwise careful riders all the time, especially on routes that they are familiar with. They "know" the traffic pattern, so are sure that they will be safe passing this line of cars. All it takes is one car that doesn't follow the general pattern and it's all over. The only way to keep yourself safe from right-turning cars or cars pulling over to the side of the road is this: don't ever pass a car on the right. Ever.

I admit that I didn't always follow this rule myself, figuring that if I had a bike lane then I was able to pass cars if they were backed up from an intersection. When I was 24. I was doing just that when one of the cars suddenly pulled into the bike lane and stopped to let a passenger out just inches in front of my wheel. I hit the back bumper hard enough to completely reshape the fork on my bike, flipped over the handlebars, and, luckily, bounced off the trunk of the car and relatively softly onto the street beside them. There were many witnesses who provided me with contact info and the driver clearly felt absolutely horrible, continually telling me that he hadn't ever seen me and he was so sorry. I believed him, but I also (at the time) felt that I had been in the right and that the accident was entirely the driver's fault. Looking back on it now, I realize that, while I may have been in the right according to the letter of the law, the accident was as much my fault as the driver's. This all happened, by the way, in the very bicycle friendly town of Eugene, OR, right next to a university campus. If it could happen in a place as bicycle aware as Eugene, especially less than a block for the University of Oregon, it could happen anywhere.

The long and short of it is that a cyclist should always assume that the drivers can't see him/her and that they are going to make an unpredictable move. This may sound paranoid, but I know it has saved me from numerous serious accidents, some of which might well have killed me.

Thursday, July 5, 2012

"Why don't you find someplace safe to ride?"

My ride to work from New Haven to Wallingford is a little under 18 miles long. I could make it in 14.5 miles, but that would mean riding straight up the Hartford Turnpike, which is safe enough for about half of the ride, but means riding in heavy-ish traffic on a two lane road with no shoulder for the other half. I choose not to take that route unless I'm running late. With me, safety is my top priority.

For this reason, I take a less direct route that puts me on a bike trail for the first 9-10 miles, then a back road for a couple of more before dealing with traffic for a bit. I then again leave the direct route to ride through a suburban neighborhood before once again joining a main road for the last dash to the office. (Unfortunately, the office is located in a business park which isn't even pedestrian friendly, let alone bicycle friendly.)

Here's a map of the route. (The big pushpins are put there by the app I use on my phone to track my progress. Feel free to ignore them.)

I am very careful when riding in the traffic-heavy parts of the route to follow all laws, including waiting for traffic lights and not going straight through from a right-turn only lane--it's not only the law; it's the safest way to ride. I also wear one of those day-glow yellow jerseys while commuting to be extra-special sure that drivers can see me without difficulty.

I tell you all of this so you'll understand the surprise I felt when the following happened while I was riding to work sometime last week.

All went very well on that morning's ride. It was a beautiful morning, the ride along the trail was very pleasant, and I was even noting that most of the drivers were treating me with more respect that is frequently the case, taking the time not to turn right just in front of me, for example. I was feeling pretty good about the whole morning when I reached the final major intersection of my ride:

This picture (borrowed from Google Maps) shows the intersection in question. (Click on the image for a full-size view.) I approach from the bottom and continue straight through to the top, taking the right turn shown at top-center. (You can't tell here, but that is a very steep climb--luckily, my office is just a little further up the hill than the building pictured, so I don't have to climb far.)

I approached the intersection just as the light was turning against me, which is not my favorite situation. To allow the cars turning right to be able to use the lane without worrying about me, I use the center lane. I stopped just ahead of the stop line so that traffic behind me could stop on the sensors and change the light for me. As it happens on that day, there were just two cars behind me. When the light turned green, I did what I always do; started to cross until I was safely out of the way of right turners and then moved right to let the cars pass before entering the narrower part of the road on the other side of the intersection. Since there were only two cars behind me, this went very well and I didn't even have to merge with any traffic as I came back into the lane to start my run for the final climb. When I was about a quarter of the way up the block to the turn, an old woman (60s, I would guess) waiting to go the other way (so I wasn't in her way or anything) rolled her window down and yelled, "Why don't you find someplace safe to ride?"

I was shocked and had no response as I passed by and turned to climb the hill. I did do some cursing under my breath, wondering what the heck her problem was. Part of me wishes I'd just stopped and educated her a bit, though that would have been stupid and exceedingly dangerous.

Regardless, the real issue is here is one of ignorance and lack of respect. This woman had no idea how far I'd ridden and to what lengths I'd gone to ride someplace safe to the best of my ability. By riding, I'm taking a car off the road, which actually makes her drive better since that's one less car clogging up the busy roads in the area. I would love to ride only in "safe" places, but I don't see them making the area bicycle-friendly in the near future. Most people treat me with respect when they see that, unlike many cyclists, I follow the laws and do my best to get out of the way of traffic whenever possible.

This woman's lack of respect was inexcusable; I have every much of a right to use the road as she did. Bicycles have been using the roads since before there were automobiles, so there's no reason why automobiles should be the only vehicles allowed on the road. Please keep that in mind.

For this reason, I take a less direct route that puts me on a bike trail for the first 9-10 miles, then a back road for a couple of more before dealing with traffic for a bit. I then again leave the direct route to ride through a suburban neighborhood before once again joining a main road for the last dash to the office. (Unfortunately, the office is located in a business park which isn't even pedestrian friendly, let alone bicycle friendly.)

Here's a map of the route. (The big pushpins are put there by the app I use on my phone to track my progress. Feel free to ignore them.)

I tell you all of this so you'll understand the surprise I felt when the following happened while I was riding to work sometime last week.

All went very well on that morning's ride. It was a beautiful morning, the ride along the trail was very pleasant, and I was even noting that most of the drivers were treating me with more respect that is frequently the case, taking the time not to turn right just in front of me, for example. I was feeling pretty good about the whole morning when I reached the final major intersection of my ride:

This picture (borrowed from Google Maps) shows the intersection in question. (Click on the image for a full-size view.) I approach from the bottom and continue straight through to the top, taking the right turn shown at top-center. (You can't tell here, but that is a very steep climb--luckily, my office is just a little further up the hill than the building pictured, so I don't have to climb far.)

I approached the intersection just as the light was turning against me, which is not my favorite situation. To allow the cars turning right to be able to use the lane without worrying about me, I use the center lane. I stopped just ahead of the stop line so that traffic behind me could stop on the sensors and change the light for me. As it happens on that day, there were just two cars behind me. When the light turned green, I did what I always do; started to cross until I was safely out of the way of right turners and then moved right to let the cars pass before entering the narrower part of the road on the other side of the intersection. Since there were only two cars behind me, this went very well and I didn't even have to merge with any traffic as I came back into the lane to start my run for the final climb. When I was about a quarter of the way up the block to the turn, an old woman (60s, I would guess) waiting to go the other way (so I wasn't in her way or anything) rolled her window down and yelled, "Why don't you find someplace safe to ride?"

I was shocked and had no response as I passed by and turned to climb the hill. I did do some cursing under my breath, wondering what the heck her problem was. Part of me wishes I'd just stopped and educated her a bit, though that would have been stupid and exceedingly dangerous.

Regardless, the real issue is here is one of ignorance and lack of respect. This woman had no idea how far I'd ridden and to what lengths I'd gone to ride someplace safe to the best of my ability. By riding, I'm taking a car off the road, which actually makes her drive better since that's one less car clogging up the busy roads in the area. I would love to ride only in "safe" places, but I don't see them making the area bicycle-friendly in the near future. Most people treat me with respect when they see that, unlike many cyclists, I follow the laws and do my best to get out of the way of traffic whenever possible.

This woman's lack of respect was inexcusable; I have every much of a right to use the road as she did. Bicycles have been using the roads since before there were automobiles, so there's no reason why automobiles should be the only vehicles allowed on the road. Please keep that in mind.

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

The Purpose of this Blog

This blog has been a long time coming. During spring, summer, and fall, I frequently ride my bicycle to work. The ride is between 15 and 22 miles, depending on the route I take, so I have plenty of time to think. Frequently, I'm thinking about what the cars around me could be doing to better handle the fact that there's a bicycle on the road. Even more frequently, I'm thinking about how clueless most bicycle riders seem, as they seem completely oblivious to the facts that (a) there are laws concerning how a bicycle is ridden in traffic (in short, they are the same as for cars except that you have to keep right whenever possible) and (b) those laws are in place to keep them safe. (Running red lights or riding on the wrong side of the street, on a sidewalk, or the wrong way on a one way street are good ways to get hit by a car.)

Because of those frequent thoughts, I first envisioned this blog as educational for drivers and bicyclists alike to learn how to peacefully coexist, and that will still be the purpose of many of the posts. Road safety isn't the only thing I think about while riding, though (and I certainly think about things that I'd like to share at times when I'm not riding as well), so I'll be sharing my thoughts and discoveries on a variety of other subjects as well. I hope you enjoy reading my thoughts and that you learn something as well. (Likewise, if you can teach me something, please feel free to do so in the comments.)

Because of those frequent thoughts, I first envisioned this blog as educational for drivers and bicyclists alike to learn how to peacefully coexist, and that will still be the purpose of many of the posts. Road safety isn't the only thing I think about while riding, though (and I certainly think about things that I'd like to share at times when I'm not riding as well), so I'll be sharing my thoughts and discoveries on a variety of other subjects as well. I hope you enjoy reading my thoughts and that you learn something as well. (Likewise, if you can teach me something, please feel free to do so in the comments.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)